Item 10: This is the big item of the night, the curfew ordinance. (Discussed previously here.)

In Citizen Comment, the speakers made all the basic arguments against the curfew:

– It does not reduce crime

– It creates unnecessary and negative interactions between kids and cops

– It can serve as an entry point for getting a kid ensnared in the legal and criminal justice system

– It’s an extra expense levied on poorer families

– It requires a high degree of officer discretion, and many of us don’t trust cops to use that discretion wisely

– Other interventions for troubled kids work better

– It targets certain people for their age, not for any misconduct.

– Plenty of cities (Austin, Waco) have done away with curfews, and it’s been fine.

– (Plus some hyperbolic arguments that overstated the dangers. Maybe they helped move the Overton window a tad.)

The presentation

Objectively, Chief Standridge has a great presentation. I don’t agree with him and I didn’t change my mind, but he’s a very good public speaker.

Here’s his basic claims:

- The fears are overstated. The implementation is very mild.

- We can run the data and show that there is no racial bias.

- The curfew is a helpful tool – both anecdotally, and based on the literature.

Here’s the longer version of the Chief’s argument:

- The fears are overstated. The implementation is very mild.

- There are 13 excused reasons that minors can be out and about during curfew. Many of the speakers ignored this list of acceptable reasons, and asked things like, “What if you’re coming home late from work?” Well, coming home from work is on the list of excuses.

- The fines tend to be at most $100 plus court fees. Not $500.

- There aren’t that many juvenile citations, and there really aren’t that many curfew citations. Pre-pandemic, there were ~15 curfew violations per year. Last year and this year, it’s about 2-3 per year. This supposedly shows good discretion by officers. It’s not being abused. Also it’s supposed to show that the police have other priorities, namely violent crime and traffic crashes.

I’ll concede part of this: as far as curfews go, this current implementation does seem to be on the milder side. However, he’s super short-staffed right now, and his focus is on violent crime and car crashes right now. Maybe next year, the focus will be elsewhere.

- Is there a racial bias?

Chief Standridge wants to unpack the claim that these stops are racially biased. The numbers look racially biased. Since 2017, there have been 87 curfew citations. (There’s a lot of problems with these numbers, but I’ll tackle that at the end. For now, let’s just go with them.)

These citations break down by race as so:

3 Black males

17 Hispanic females

40 Hispanic males

16 white males

Zero white females or black females

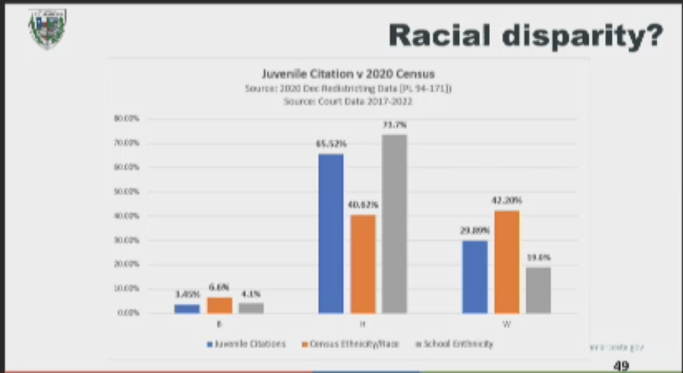

Here’s how the chief spins this: “I admit it looks bad when you compare to census data. Hispanics are only 40% of the population in town, but they’re 65% of these citations. But remember, most of these were daytime truancy tickets! The right comparison is to the SMCISD demographics. And SMCISD is 73% Hispanic, so we’re actually not targeting Hispanic students disproportionately, after all!”

Alyssa Garza goes after him for sloppy data and mixing which data he wants to use. This is a thing that public policy folks have to be extremely careful about – how exactly are you coding race? Federal data calls Hispanic people “white”, which is a choice that feels at odds with how everyone thinks about race. Is he using self-identified race? How reliable are these numbers?

I’m also skeptical of his comparison. If he wants to use SMCISD data as his comparison group, then he needs to separate out the truancy data from the overnight data. What are the demographics for the 35% that are overnight violations? Where kids live in “certain” neighborhoods, as the chief put it last time?

- The curfew is a helpful tool – both anecdotally, and based on the literature.

Next, he gets some anecdotes from cops that this ordinance has caused minors to change their behavior for the better. It keeps students at Lamar/Rebound on campus. There were gang kids involved with guns and shoot outs. There was a suicidal kid who was reconnected with their parents, back in 2001.

(This gang business is problematic, but I’m leaving that alone for today.)

Last time, Alyssa Garza specifically asked what percent of violent crimes are committed by minors in San Marcos. I want to know this, too, and it should be easy to acquire. He did not provide that data, which makes me speculate that it’s negligible.

The literature: Standridge acknowledges that the evidence is thin on curfews actually reducing violent crime. However, curfews help keep kids from being victims of crimes. And possibly they end up committing less crimes later on in life.

He also discusses truancy. Truancy is entirely separate from the police department. The elementary and middle schools all have attendance committees and parent liaisons and make home visits. (He didn’t say what the high schools do. But school funding is tied to attendance, so I’m guessing they have a lot of people dedicated to it.) He has talked with Judge Moreno about the extent and outcomes of truancy cases she sees: it’s a lot.

To me, the discussion of truancy court makes the opposite point – that the schools have an established system for kids who miss school, and the world won’t fall apart if curfew is ended.

My analysis:

First, Chief Standridge is focused on “Which kids are helped by the curfew?” The activists during citizen comment were all focused on “Which kids are hurt by the curfew?” Fundamentally, they are each focused on different groups of people. And look: life is messy. Both could be true – some kids can be helped, while others are hurt. The question is how to weigh and decide which of those claims gets priority.

Are kids helped by the curfew, like he claims? I’m skeptical of his anecdotes. For the kids carrying guns around, the cops can already intervene. For the kids who want to leave Lamar campus, I suppose the threat of a $50 fine could motivate them to stay put.

Does curfew protect minors from victimization, like the literature shows? Sure! I can believe that minors are protected from certain kinds of crimes if they obey curfews. On the other hand, this is a bit close to “lock up your daughters so they don’t get raped” territory.

But also: when we say that minors are less likely to be victims under a curfew, what kinds of crimes are we measuring? Is domestic violence included in that statistic? Because when people are trapped at home – like during covid – domestic violence increases a lot.

Now on to the activists’ side: are kids hurt by the curfew? It’s not automatically traumatizing to all kids to get stopped and asked why you’re out at 3 am. But most of these kids have seen the videos of cops shooting black and brown men, and then, if you’re black or brown, it might be terrifying. I’m not sure Chief Standridge fully gets what a trust-deficit the police have. And he also glosses over the idea that he may have racist officers that are rougher with black and brown kids than with white kids. (He’d be foolish to pretend he has no chance of having MAGA police officers.)

Finally: some kids would just like to wander around at night, and they’re not going to be destructive jerks about it. We generally take civil liberties extremely seriously. You need to have a compelling reason to remove someone’s freedom.

One final thought: You maybe could probably talk me into the daytime truancy curfew more easily than the late-night curfew. I can see a clear, direct benefit to kids to making sure they get that high school diploma. But you need to be talking with the school district, and as far as I can tell, the school district hasn’t been involved at all.

So what do our councilmembers do?

Everyone is more uneasy about the curfew now. Last time, the focus was on crime in neighborhoods and how this curfew was good for everyone else. The focus was not on the kids (besides Max and Alyssa). Even Mark “gunshots every day outside my house!” Gleason is now thinking about actual juveniles, and he is worried that home schooled kids will get caught up in the truancy curfew. (The ordinance gets amended to include home schooling as a defense to prosecution.)

Saul proposes that the whole thing get sent back to committee for further drafting.

Jane Hughson says, “Back? It never was in a committee.” But nevertheless, Saul’s proposal sets things in motion.

Alyssa Garza always makes the most sense. But tonight, Shane Scott makes the second-most sense. He basically says, “The speakers were convincing and the chief was also convincing. But when I was a kid, I was allowed total freedom as long as I didn’t get in trouble. I just don’t like constraining anyone’s freedom if they’re not doing anything wrong.”

Alyssa Garza makes the best points. Basically, it’s complicated:

- What about kids with informal jobs?

- What about kids avoiding violent or unsafe homes?

- Can we involve more players at the table?

This is exactly right. The reasons that a kid might be out at 3 am are big and complicated, and sometimes innocent and totally fine. Let’s bring social services and Community Action and the schools into the conversation, instead of being authoritarian about it.

Last time, Max Baker made an amendment to cap the citation at $50, plus court fees. Mark Gleason was the only person to vote against the cap.

This meeting, Mark Gleason tries to undo it. He makes a motion to allow penalties of up to $100 plus court fees, because he’s a jerk because he mistakenly believes that stiffer penalties are a bigger deterrent to bad decisions. (Actually, if you want to deter crime, you should have small, predictable consequences. The main problem here is that getting caught is extremely erratic, not the size of the penalty.)

But no one seconds Mark’s motion, and I enjoyed listening to the silence drag out. The malevolent little amendment gasped for breath, and died.

The curfew expired at the beginning of November. So currently, there is no curfew ordinance. (Children! Go run nuts! All hell has broken loose!) The question is:

- Should this get sent to the Criminal Justice Reform Committee, and then renewed when they come back with their recommendations?

- Or should this get renewed, and then sent to the CJR committee, and then revised when they come back with recommendations?

Alyssa makes a motion for the first option.

The vote to postpone without renewal:

So that fails. (Alyssa mutters “y’all are so fake” quietly.)

They unanimously agree to send it to the Criminal Justice Reform committee.

Should it be approved in the meantime?

One technicality: this is still the first reading. Last time, the first reading never passed. So this still has one more reading to go through.

…

Post Script #1: Just for funsies, let’s dunk on “defenses to prosecution” for a moment:

#9: Anyone between the ages of 10-17 who is married can be out past curfew. What the fuck is going on with that?

This ordinance was originally written in 1994. You know what it was intended to mean back then, of course: if an underage girl has married an adult man, and she’s out past curfew, then you wouldn’t take her home to her parents anymore. She’s married into the adult class of people now, and her husband deserves all deference on the matter. It is super-duper creepy as hell!

Furthermore, it doesn’t stand up to the barest of logic. An underage married person isn’t at risk of being a victim of crimes? An underage married person can’t commit crimes? Doesn’t need to finish high school anymore?

Honestly, show me a 17 year old married girl, and I actively want someone pulling her aside and asking if she needs help. Most likely, she either got pregnant, or she was escaping something worse at home. Either way, she could probably use a hand.

…

Post Script #2: The the data from Chief Standridge’s presentation is kinda gibberish.

Exhibit A:

Brought to you in patented squint-o-vision, because I had to take a screen shot, because it doesn’t appear in the packet.

At 1:49:45, Chief Standridge is partway through this slide, and he talks about the green area on the far right, Curfew Citations. He says “the raw number of citations for 2022 is two.” So I’m inferring that the 3rd-from-right column is the raw number of curfew citations for the past five years. Add those up: 17+14+11+3+2=47 curfew violations over the past five years.

However, no one refers to 47 as the total curfew violations. The total violations cited everywhere is 87 citations for the past five years. It’s in both the presentation, it’s used throughout the discussion, and it’s in the police memo from the packet.

Chief Standridge uses the smaller numbers to illustrate how sparingly this is used, but uses the bigger numbers to talk about demographics and how there’s no racial bias. It’s weird and I don’t understand the disparity between the two numbers.

But wait! There’s more!

Exhibit B: Here’s how the 87 breaks down racially:

Standridge computes the percentages black/Hispanic/white from this. Here’s how he gets his percents:

3 Black kids out of 87 total violations: 3/87 = 3.45%

17 females + 40 males = 57 Hispanic kids out of 87 total violations: 57/87 = 65.52%

26 white kids out of 87 total violations: 26/87 = 29.89%.

See how there are 26 white kids, instead of 16? That’s because 3+17+40+1+16=77 total citations, not 87 citations. There are 10 unaccounted kids in his racial breakdown, and so he made them all white. (And maybe it is just a typo. It could be that the true number is actually 26 white kids, not 16.)

Those are the percents for the blue bars in this chart:

I know, it’s miserable to read that chart. But the three blue bars are labeled 3.45% on the far left, 65.52% for the middle blue bar, and 29.89% for the blue bar on the right.

(That graph is supposed to be the defining argument that the curfew isn’t being administered in a racist way. He’s comparing the blue curfew citations with federal census racial demographics (orange), and SMCISD racial demographics (gray). Each cluster of three bars is a different race, with Black kids on the left, Hispanic kids in the middle, and white kids on the right.)

What’s the correct computation, then? You need to change the denominator. You only know the demographics of 76 kids, so you must compute the racial percents out of 76.

Here are the correct percents:

3 Black kids out of 76 violations: 3/76 = 3.95%

57 Hispanic kids out of 76 total violations: 57/76 = 75%

16 white kids out of 76 total violations: 16/76 = 21.05%

I don’t think this is part of some big conspiracy where Chief Standridge is intentionally massaging the data. I do think he’s spouting a bunch of gibberish, because he’s got inconsistent numbers handed to him, and he went with what was most expedient to serve the narrative he wanted to tell.